DiDi has become a digital banking giant in Latin America

Attempting to directly replicate the "perfect model" used domestically will not work; we can only earn respect by demonstrating our ability to solve real problems.

On the other side of the globe, DiDi is no longer just a ride-hailing company earning commissions, but has become a digital banking giant. The financial business, once considered an appendage to ride-hailing, now boasts over 25 million users in Latin America.

If we focus on China, DiDi’s image is clear and fixed. Despite having hundreds of millions of monthly active users, in the more lucrative financial sector, it remains an awkward outsider in the face of the impregnable walls built by WeChat Pay and Alipay, confined to its small territory of transportation.

However, on the bustling streets of Mexico City and in the congested traffic of São Paulo, thousands who have never set foot in a bank clutch their first Mastercard, emblazoned with the DiDi logo.

Here, it is not only the driver taking people home, but also the true master of underlying capital flows—the “wallet” that countless ordinary Latin Americans rely on for survival.

Looking back at DiDi’s rise in Latin America, this is not just a geographical expansion, but more like a “reverse evolution” forced by the environment.

In China, because the roads were already built, DiDi only needed to be the driver; but in Latin America, faced with a barren landscape, it was forced to learn how to build roads and bridges. This infrastructure-building skill was something Chinese internet companies excelled at in their early days, but gradually forgot as domestic infrastructure became too perfect.

Ambitions Strangled by “Perfection”

DiDi’s failure on China’s financial battlefield was not because it did anything wrong, but because it was born in an overly mature era, where the market’s infrastructure was already too perfect. Perfection, sometimes, is a curse.

In the grand narrative of China’s internet business history, 2016 was a watershed year. That year, as WeChat Pay and Alipay swept across the country, China’s mobile payment war was essentially over. The two giants together occupied over 90% of the market, turning mobile payments into a national-level infrastructure as accessible as water, electricity, and gas.

For consumers, this was ultimate convenience; but for latecomers like DiDi, it was an invisible high wall.

In the following years, DiDi went to great lengths to acquire eight financial licenses, including payment, online microloans, and consumer finance, attempting to build its own closed loop. But when the two giants had already become the underlying operating systems of the business world, other payment tools could only be functional plugins attached to this system.

The deeper paradox is that traffic has never naturally equaled “retention.”

Although DiDi has a huge customer base, the travel scenario has a fatal genetic flaw—short stays and no retention. In the ultimate payment environment built by the two giants, funds are transferred from the user’s bank card to the driver’s account and then quickly withdrawn.

In this process, DiDi is just an efficient pipeline, not a reservoir of funds. Compared to the capital retention generated by Alibaba’s e-commerce transactions and the fund flows from Tencent’s social red envelopes, DiDi’s traffic is “use and go.”

This suffocating feeling ultimately peaked amid drastic regulatory changes.

The app takedown storm in the summer of 2021, followed by a massive 8 billion yuan fine, acted as heavy pauses that completely ended DiDi’s financial ambitions in China. Under such high pressure, DiDi not only missed the window for expansion but also lost room for strategic maneuvering. It could only shrink back and survive cautiously.

Official notice of DiDi’s app takedown

At this point, DiDi’s financial story in China seemed to have reached its end.

It was trapped in a “perfect” fortress. The roads were too smooth to need building; the bridges too stable to need construction.

This seemed like an unsolvable deadlock. But across the Pacific, a completely different business script was unfolding. There, the barrenness did not become an obstacle, but instead became DiDi’s greatest advantage.

Rebuilding Trust in the Land of Cash

When DiDi’s vanguard first set foot on the Latin American continent, what they saw was not a blue ocean waiting to be developed, but a huge social fault line.

According to the World Bank, about half of adults in Latin America do not have a bank account. In Mexico, with a population of 130 million, this means over 66 million ordinary people are shut out from the modern financial system.

This is a suffocating “financial vacuum.” In this vacuum, cash is the only faith.

In Mexico, nearly 90% of retail transactions are still completed in cash. For Chinese internet companies used to a cashless society, this “cash worship” is nothing short of a nightmare. In China, funds flow in the cloud—clean and efficient; but in Latin America, since most passengers don’t have bank cards, they can only pay fares with crumpled, even sweat-stained bills.

This directly led to a collapse in efficiency. Drivers collected bags of change, but the DiDi platform could not take a cut, and many drivers were banned for arrears, nearly paralyzing the system.

But even more frightening than inefficiency is out-of-control security.

On the crime-ridden streets of Latin America, drivers carrying large amounts of cash became mobile “ATMs.” Robberies were rampant, and every stop to collect payment could be a life-or-death gamble.

Here, we must introduce the most important reference: Uber.

As the pioneer of ride-hailing, Uber entered Latin America before DiDi. But faced with the same cash problem, Uber’s choices reflected a fundamental strategic difference between Eastern and Western internet giants.

Uber represents the typical “Silicon Valley cleanliness”—professional division of labor. In the mature US market, finance belongs to Wall Street, and Uber only does the connecting. This mindset led them to stubbornly stick to what they were good at, even in the barren lands of Latin America.

The price was painful. In 2016, Uber suffered a literally “bloody lesson” in Brazil. After being forced to accept cash payments, the number of robberies targeting drivers soared tenfold in just one month. According to Reuters, at least six drivers lost their lives as a result.

Faced with this surge in deadly risk, Silicon Valley’s usual choice is to retreat and wait for the environment to mature.

But DiDi represents the “super app” mentality of China and Asia: all-round supplementation.

Companies that grew up in China’s brutal business street battles know one thing: if society lacks roads, you build them; if society lacks credit, you create it.

Therefore, DiDi chose a heavier, more down-to-earth, but also more effective path—it decided to transform the environment.

DiDi set its sights on the red and yellow signs of OXXO convenience stores, ubiquitous on Mexican streets.

Mexico’s national convenience store

This retail giant, with 24,000 stores, handles nearly half of Mexico’s cash transactions and is the de facto “national cashier.” DiDi keenly spotted this connection point and made a very Chinese-style pragmatic decision: turn convenience stores into its own human ATMs.

A silent financial experiment began.

When a driver finishes a day’s work with pockets full of cash, he no longer needs to nervously take the money home. Instead, he parks at an OXXO, shows the clerk the barcode in the DiDi App, and hands over the cash. With a crisp beep from the scanner, the physical bills instantly become a digital balance in the DiDi Pay account.

This crisp beep is highly significant.

This is not just a top-up, but a ferrying of offline cash to the online world. By leveraging the ubiquitous convenience store network, DiDi built a low-cost, independent fund transfer system outside the traditional banking system.

Once funds enter DiDi Pay, DiDi is no longer just a ride-hailing platform—it has become the driver’s “shadow bank.”

DiDi then quickly built application scenarios on top of this account. In Brazil, DiDi’s 99Pay deeply integrated with the local instant payment system PIX, allowing tens of millions of grassroots people to enjoy the dignity of instant financial settlement for the first time.

This approach built a moat “with blood”: safety.

In China, mobile payments are for “speed”; but in crime-ridden Latin America, mobile payments are for “survival.”

Every attempt to go cashless means one less risk of a driver being robbed at gunpoint. When a driver finds that using DiDi Pay frees him from fear, his loyalty to the platform will surpass any commercial subsidy.

At this point, DiDi finally built its first expressway in Latin America. It solved not a “nice-to-have” need, but the continent’s most urgent desire—to make money flow and transactions safe.

When Footprints Become Credit

Once the road was built, DiDi suddenly realized it was standing on an untapped gold mine—data.

But the data here does not refer to traditional financial records. In Mexico or Brazil, the vast majority of drivers and passengers are blank slates in the records of traditional financial institutions. Banks can’t see them, don’t know if they can repay, and thus dare not lend to them.

Banks can’t see, but DiDi can.

Through its app, DiDi has an almost omniscient “God’s-eye view.” It knows exactly when a driver starts work each day, how many kilometers he drives, and whether he is diligent; it also knows where a passenger lives, works, and how frequently they spend.

These seemingly trivial travel footprints are recoded by DiDi’s risk control model and transformed into a new type of credit—“behavioral credit.”

This is a warmer assessment than bank statements. A driver who sets out at 6 a.m. every day, rain or shine, even if he has no bank savings for various reasons, is still a highly creditworthy customer in DiDi’s algorithm. Diligence, for the first time, is priced as credit here.

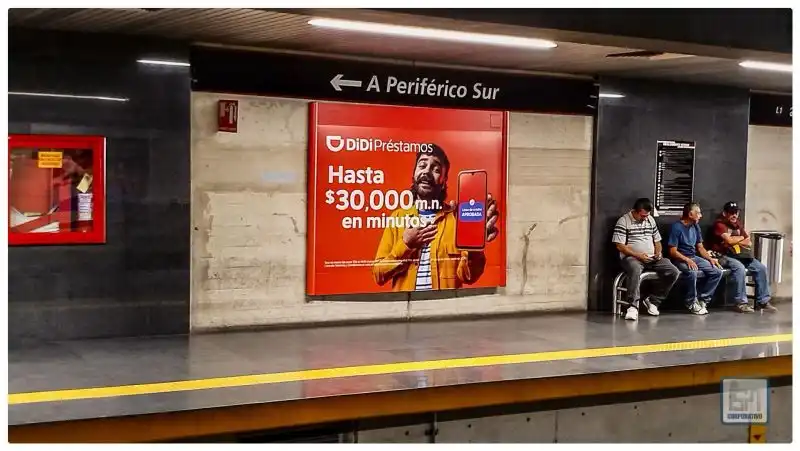

Based on this endogenous credit creation, DiDi naturally launched the loan product “DiDi Préstamos.” For millions of Latin American users, this may be the first time in their lives they have received formal financial credit. Data shows that about 70% of DiDi’s loan users had never borrowed a cent before.

Local advertisement for DiDi Préstamos

This is not only a commercial breakthrough but also a profound sociological experiment.

In Latin America, the vast “grey economy” population has long been invisible due to a lack of credit records. DiDi inadvertently accomplished a “digital confirmation of rights” that governments had failed to achieve for decades. A street taco vendor or a used car driver, by joining DiDi’s ecosystem, gained a recordable economic identity for the first time and stepped out of the shadows into the sunlight.

This ability to “formalize the informal economy” is the deepest root of DiDi’s presence in Latin America.

The moat built by this evolution is astonishing, even sparking a “genetic” war in Latin America.

The digital finance battlefield in Latin America is already fiercely contested, with digital banking giants like Nubank and e-commerce titans like Mercado Libre. But DiDi has a dimensional advantage they lack: extremely high-frequency life scenarios.

Nubank’s DNA is banking—low frequency; Mercado Libre’s DNA is e-commerce—medium frequency. DiDi’s DNA is transportation—high frequency.

You might shop online once a month, visit a bank a few times a year, but you go out every day. In cultivating payment habits, “transportation” is the highest-level battlefield. DiDi, with its high-frequency ride-hailing and food delivery (DiDi Food), successfully broke through the low-frequency barriers of financial services.

Having traffic is not enough; you also need “retention.”

To completely intercept the rapidly circulating funds on its platform, DiDi unleashed its ultimate weapon: leveraging Latin America’s high-interest environment to launch an interest rate war.

It launched the savings product “DiDi Cuenta” with an annual yield as high as 15%. This is a figure that would sound almost crazy in China and might even be suspected as a Ponzi scheme. But in Mexico, where the benchmark interest rate remains in double digits, this is just a routine battle among digital banks for deposits.

DiDi simply adapted to local customs, but in doing so completed the most critical turning point—it finally shed the awkward role of a “pass-through god of wealth” and truly became a reservoir for accumulating wealth.

Industrial Synergy

Once the credit system and fund pool took shape, DiDi’s ambitions were no longer limited to finance itself.

It began to play a more strategically significant role: the “Trojan horse” for Chinese industry going global. It aimed to use finance as the key to unlock the door to heavy-asset consumption in Latin America.

The first wave was the export of consumer goods.

In 2025, Alibaba’s AliExpress partnered with DiDi in Mexico to launch a “buy now, pay later” service. The effect was immediate—during the promotion week, AliExpress’s order volume soared by 300%, and some Chinese merchants saw sales surge 18-fold.

For young Mexicans without credit cards, the credit payment provided by DiDi became the bridge connecting them to “Made in China.”

But this was just the prelude. The deeper layout is happening in the overseas expansion of China’s high-end manufacturing, especially new energy vehicles.

Today’s Latin America has become the new battleground for Chinese carmakers like BYD, Chery, and Great Wall. However, the biggest obstacle they face is not product strength, but the lack of financial tools. Local drivers want to buy electric cars to save on fuel, but Latin American banks, with ineffective risk models, not only approve loans slowly but often reject them outright.

At this point, DiDi became the crucial connector.

DiDi holds millions of drivers needing new cars in one hand, and precise risk control data and credit funds in the other, connecting them with Chinese carmakers eager to enter the market. It not only issues credit cards to drivers but also directly acts as an auto finance service provider.

Through DiDi’s financial solutions, drivers can buy Chinese-made electric cars in installments and repay the loan with their ride-hailing income.

This is a deeply integrated industrial synergy. DiDi is becoming the infrastructure for Chinese high-end manufacturing in Latin America. It is not only paving the way for finance but also for the energy transition.

At this point, a complete closed loop finally surfaced.

In Latin America, DiDi has transformed itself into a super interface connecting online and offline, linking Chinese manufacturing with Latin American consumption.

The “super app” dream that DiDi could not realize in China due to a mature environment has, on the barren lands of the other side of the world, miraculously become reality in the most primitive yet resilient way.

The Builder’s Instinct

With 1.162 billion orders in a single quarter, 35% revenue growth, and nearly 30 billion in transaction volume, DiDi’s solid financial report has set a new milestone for Chinese internet companies going global.

This achievement signifies not only commercial success but also a revision of the logic behind the “China model going global.”

In the past, we often believed that with technological and efficiency advantages, China’s mature internet model could be directly transplanted to emerging markets. But DiDi’s experience in Latin America proves that simple copying is a dead end. You can’t just bring advanced machines; you also have to redo the dirty and tiring work done when those machines were first built.

The most crucial thing DiDi did right in Latin America was to completely let go of the arrogance of a tech company. It got down to earth, went back ten years, and redid the QR code promotions and cash-based grassroots marketing that Alipay and WeChat Pay once did, but this time in a foreign land.

We used to think China’s model excelled in algorithms and efficiency. But DiDi’s story shows that the most formidable ability of Chinese companies is the builder’s instinct to “create something from nothing” in a resource-poor environment.

In China, this instinct was sealed away by overdeveloped infrastructure. DiDi was trapped between WeChat and Alipay, able only to be an efficient dispatcher. But in Latin America, thrown into a barren land, this suppressed gene exploded. It did not see itself as a lofty tech company, but lived as a humble “infrastructure foreman.”

This also foretells a certain destiny and opportunity for Chinese companies going global: trying to directly transplant the domestic “perfect model” won’t work. We can only win respect by exporting the ability to “solve pain points.” In those emerging markets that are as noisy, chaotic, and full of longing as China was a decade ago, lies the biggest Easter egg of the second half of China’s internet story.

Disclaimer: The content of this article solely reflects the author's opinion and does not represent the platform in any capacity. This article is not intended to serve as a reference for making investment decisions.

You may also like

Gensyn launches two initiatives: A quick look at the AI token public sale and the model prediction market Delphi

Gensyn previously raised over 50 million dollars in total through its seed and Series A rounds, led by Eden Block and a16z, respectively.

Verse8's Story: How to Support Creative Expression in the Age of AI

Creativity will continue to increase in value through collaboration, remixing, and shared ownership.

ECB shifts stance! Will interest rate hikes resume in 2026?

In the debate over "further tightening" versus "maintaining the status quo," divisions within the European Central Bank are becoming increasingly public. Investors have largely ruled out the possibility of the ECB cutting interest rates in 2026.

On the eve of Do Kwon's trial, $1.8 billion is being wagered on his sentence

Dead fundamentals, vibrant speculation.